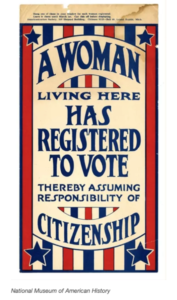

In honor of Women’s History Month, we reflect on the pivotal moment of August 18, 1920, when the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified, prohibiting the government from denying citizens the right to vote on the basis of sex, extending the right to vote to women. This landmark achievement was not only a victory for gender equality but also a testament to the resilience and determination of countless women across the nation. Tens of thousands of women in Boston, including 3,000 in Charlestown, seized their opportunity to participate in shaping democracy by registering to vote. Through the meticulous transcription efforts of the Mary Eliza Project, the stories of these women have come to light, offering a glimpse into their lives and contributions to society. As we celebrate Women’s History Month, let us honor the bravery and tenacity of the Charlestown women who registered to vote in 1920, recognizing their invaluable role in advancing the cause of equality and democracy.

Get-out-the vote efforts resulted in a registration process that played out differently depending on an individual’s race, ethnicity and geographic location. “The 19th Amendment was ratified, but it was up to each state to change their electoral administration.” While some states (predominantly in the south) deliberately blocked women from voting, Massachusetts and Boston emerged as a bastion of democracy.

Before the ratification of the 19th Amendment, in 1879, Massachusetts women won voting rights in School Committee elections. In preparation of the 19th Amendment, city and state officials encouraged women to register to vote in these voting registries because they would automatically become registered in state and federal elections. Upon receiving confirmation of ratification, Boston Mayor Andrew Peters extended registration deadlines, urging “the women of Boston [to] show the way in exercising the newly conferred power.” The women of Boston responded to their new status as full voting citizens by educating themselves, registering to vote, and voting in their first federal election on November 2, 1920.

Before the ratification of the 19th Amendment, in 1879, Massachusetts women won voting rights in School Committee elections. In preparation of the 19th Amendment, city and state officials encouraged women to register to vote in these voting registries because they would automatically become registered in state and federal elections. Upon receiving confirmation of ratification, Boston Mayor Andrew Peters extended registration deadlines, urging “the women of Boston [to] show the way in exercising the newly conferred power.” The women of Boston responded to their new status as full voting citizens by educating themselves, registering to vote, and voting in their first federal election on November 2, 1920.

The Massachusetts’ state primary occurred on September 7, which only gave about 31,500 Boston women time to register. In the months between the state primary and the elections, thousands more women registered to vote in greater Boston. The record of new registered voters shattered daily, and the Mayor of Boston ordered registration locations to stay open past 10pm and hired more election officials to help register new voters. When voter registration closed, more than 70,000 women had registered.

Through a Community Preservation Act Grant, the City of Boston Archives is transcribing 160 handwritten volumes of General Registers of Women Voters from the City of Boston (August to October 1920). The Mary Eliza Project is named after the pioneering African American nurse and civil rights activist Mary Eliza Mahoney, one of many Boston women who registered to vote in 1920. The transcribed data is available to the public as a fully searchable and sortable excel spreadsheet and can be found at this link.

The 1920 Women’s Voter Registers document the names, addresses, places or birth and occupations of these women. Sometimes additional information about their naturalization process to become a US citizen was provided, including where their husbands were born because in 1920, a woman’s citizenship status was tied to her husband’s nationality. This dataset allows us a glimpse into Charlestown’s residents in the early twentieth century.

In 1920, Charlestown encompassed Wards 3 and 4. Ward 3 included the Western part of Charlestown: Sullivan Square area to Austin / Cordis / Cross Street boundary, and Ward 4 covered the Monument Square and Town Hill areas to the Navy yard. Over 1600 women living in Ward 3, and 1400 in Ward 4 registered to vote in the summer and fall of 1920. Most of Charlestown’s new voters were born in Massachusetts, but the neighborhood was also home to 687 women born in Canada, England, French West Indies, Germany, Ireland, Italy, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Russia, Scotland, Sweden and Wales, of those, 502 were born in Ireland. In Ward 4 almost ⅓ of the women who registered to vote were born outside of the United States.

More than half of the women who registered to vote in Ward 4 worked outside of the home. While many women worked in domestic service and factories, many were employed in the Charlestown Navy Yard as Yeomen. Women in Ward 3 worked as sugar packers, telephone operators, forewomen, box makers, florists, teachers, stenographers, clerks, housekeepers, tailors, accountants and “at home”.

More than half of the women who registered to vote in Ward 4 worked outside of the home. While many women worked in domestic service and factories, many were employed in the Charlestown Navy Yard as Yeomen. Women in Ward 3 worked as sugar packers, telephone operators, forewomen, box makers, florists, teachers, stenographers, clerks, housekeepers, tailors, accountants and “at home”.

45 year old Agnes McAuliffe of 36 Adams Street registered to vote on October 4, 1920. While she gave her place of birth as New Zealand, her father was born in Ireland and was naturalized in Boston US Circuit Court in 1878, when Agnes would have been only three years old. As a single woman with a naturalized father, Agnes had to produce his naturalization papers to claim her right to vote. She worked as a “packer” in 1920. Further research reveals that Agnes arrived in the United States 1882, never married and lived as a “roomer” on Adams Street.

45 year old Agnes McAuliffe of 36 Adams Street registered to vote on October 4, 1920. While she gave her place of birth as New Zealand, her father was born in Ireland and was naturalized in Boston US Circuit Court in 1878, when Agnes would have been only three years old. As a single woman with a naturalized father, Agnes had to produce his naturalization papers to claim her right to vote. She worked as a “packer” in 1920. Further research reveals that Agnes arrived in the United States 1882, never married and lived as a “roomer” on Adams Street.

49 year old Hannah Barry of 43 Lexington Street gave her husband Edward’s naturalization papers to the Election Clerk. Both were born in County Cork, Ireland, but only Edward was naturalized through the courts. Because of a 1907 law linking a woman’s citizenship status to her husband’s nationality, Hannah gained her citizenship status through her husband’s naturalization. She was widowed prior to registering in 1920 and worked as a housekeeper in the Lexington Street house. Further research reveals that #43 Lexington was a small cottage located in the rear of #45, that Hannah’s husband Edward died in 1920, and they lived with two fisherman “roomers”. Both houses have been demolished to make way for the Bunker Hill Housing Development, and this leg of Lexington Street is now O’ Meara Court.

This dataset is an incredible resource, providing a glimpse into the Charlestown culture in the early twentieth century. There are many more stories waiting to be uncovered. We hope that you can find the records of your ancestors, and women that lived in your house in 1920.

We have sorted through the dataset and host all of Charlestown’s women voting records from 1920. Charlestown’s women’s voting records can be found at this link.

1.Smithsonian Magazine, “What First Women Voters Experienced When Registering for the 1920 Election,” Smithsonian Magazine, accessed March 1, 2024, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/what-first-women-voters-experienced-when-registering-1920-election-180975435/

2.Ibid

3.Boston Herald, “31,517 Women to Vote in Boston,” September 5, 1920. Boston Herald, “70,112 Boston Women to Vote,” October 23, 1920.

4.Smithsonian Magazine, Ibid

5.Boston Herald, “Registration Record of City Broken when 9468 New Voters are Added,” October 12, 1920.

6.National Park Service, “Boston Women in the 1920 Election,” National Park Service, accessed March 11, 2024, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/boston-women-in-the-1920-election.htm.

7.Boston.gov, “Mary Eliza Project: Ward 3 Voter Records Now Available,” Boston.gov, accessed March 11, 2024, https://www.boston.gov/news/mary-eliza-project-ward-3-voter-records-now-available.

8.Boston.gov, “Mary Eliza Project: Ward 4 Voter Records Now Available,” Boston.gov, Accessed March 9, 2024. https://www.boston.gov/news/mary-eliza-project-ward-4-voter-records-now-available

9.Boston.gov, “Mary Eliza Project: Ward 3 Voter Records Now Available,” Boston.gov, accessed March 11, 2024, https://www.boston.gov/news/mary-eliza-project-ward-3-voter-records-now-available.

10.Boston.gov, “Mary Eliza Project: Ward 4 Voter Records Now Available,” Boston.gov, Accessed March 9, 2024. https://www.boston.gov/news/mary-eliza-project-ward-4-voter-records-now-available

COMMENTS

There aren't any comments yet.

Comments are closed.