February 19, 2024

On the site of 36 Belmont Street in Charlestown lived the Walker family, a prominent Black family with a very rich history. While the former Walker house at 36 Belmont Street was demolished, and eventually the present house designed by Timothy Sheehan in 2007 took its place, it is important to understand who formerly lived here to tell a fuller history of Charlestown.

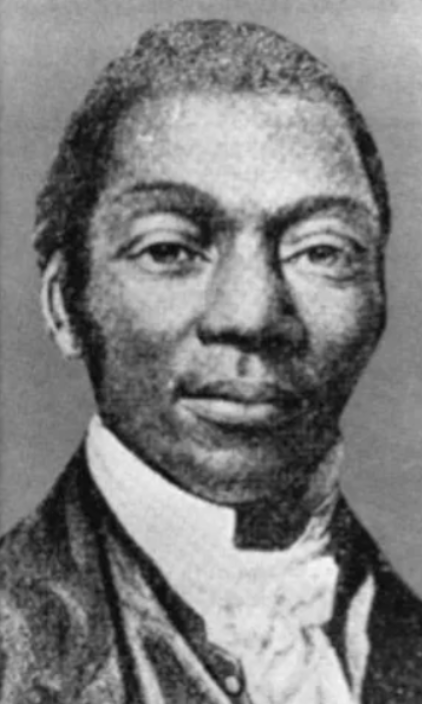

Eliza Butler, of a free Black family in Boston, in 1826 married David Walker, a formerly enslaved person born in North Carolina who escaped to Boston just years prior. David set up a clothing shop on Brattle Street in Boston and in 1827 he became the Boston agent of the first Black-owned and operated newspaper in America, Freedom’s Journal, making contributions both monetarily and through his writing. In 1829, he published his famous “An Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World”, a call for Black unity and a fight against slavery. The pamphlet was distributed all over the South and became a hated object among many because David Walker demanded an end to slavery, by force from Black people if necessary. On June 28, 1830, David Walker was discovered dead in the doorway of his shop on Brattle Street in Beacon Hill, leaving his young pregnant wife Eliza a widow.

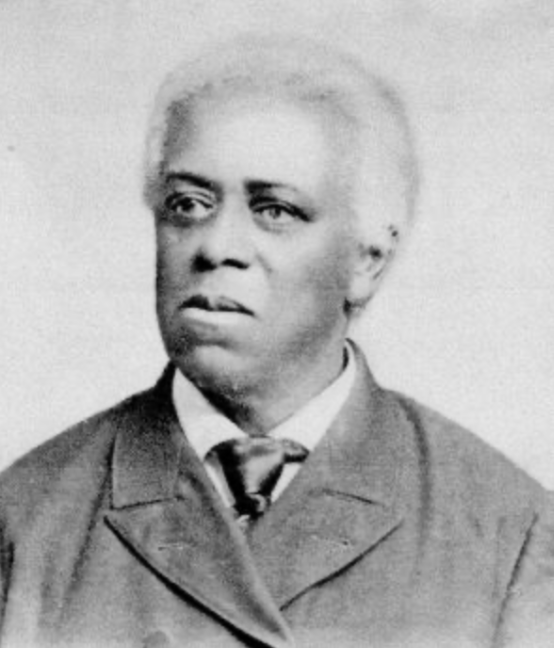

David and Eliza’s son Edward Garrison (Edwin) Walker was born around 1830. Shortly after David’s death and Edward’s birth, Eliza remarried to Alexander Dewson and the family moved to Bunker Hill Street in Charlestown. By 1845 Eliza purchased a plot of land on Belmont Street that had been carved out of a larger plot of land owned by Solomon Hovey in 1837, and a house was built shortly thereafter. Edward Garrison Walker grew up in Charlestown, attended public schools, and learned his trade as a morocco dresser (leatherworking) and became successful by 1857, he had 15 men working for him in his own shop on Medford Street.

In 1859 Walker married Hannah Jane Van Vronker, and had 3 children: Edwin Eugene (1859-1891) Georgiana Grace (1861-?) and Eliza Ann (1863-1866.) The family lived with E.G.’s mother Eliza on Belmont Street.

Edward was very active in the abolitionist movement, he would often travel from Charlestown to Boston to participate in meetings, protest and encourage integration. He spoke in opposition to efforts promoting Black emigration, stating that the United States was the home of African-Americans, and it was better to stay and fight. He fought to become a member of the Monument Division of the Sons of Temperance after the organization ruled that it was possible for an African-American to join the group.

Walker, along with other prominent abolitionists Lewis Hayden and Robert Morris, were lauded by the Boston public in 1851 for their assistance in obtaining the release of Shadrach, a fugitive slave. This legal battle piqued Edward’s interest in law. Edward used his savings as a leatherworker to purchase legal books and was admitted to the Suffolk bar in 1861, becoming the fourth African-American to practice law in Massachusetts. Walker ran for the Massachusetts House of Representatives, winning his Charlestown district, largely populated by Irish laborers. Edward Walker was for a time, the only Black member of a secret order of Irish men in Charlestown, showing his devotion to Charlestown residents.

In 1866, Massachusetts was one of only 6 states that allowed Black men the right to vote. Walker ran for the Massachusetts House of Representatives, winning a district with only 3 Black registered voters by 19 votes. He was elected alongside another African-American, Charles L. Mitchell of Boston, and they often argued over who had been elected first. Walker made the most valid claim since Charlestown’s polls had closed an hour earlier than Boston.

While serving in the 1867 Legislature, he voted to prevent the merger of Charlestown with Boston stating that this was what his constituents desired then. He was one of the pioneers of women’s suffrage, and he opposed the 14th amendment as drafted, arguing that its language contained insufficient guarantees against race-based discrimination and disenfranchisement. As a result, Walker’s opposition was a breach with his fellow Massachusetts Republicans. They did not nominate him for a second term. He in turn joined the Democratic party and was among the first Black men in Massachusetts to join the Democratic Party as one of many Boston African Americans to switch parties due to dissatisfaction with the Republicans.

After his single term in the Legislature, Walker went back to his legal practice and along with his friend Robert Morris, became the two most financially successful black lawyers in Boston. When Robert Morris died in 1882, Walker gave the principal eulogy at the memorial service at the Charles Street A.M.E. Church and his remarks were reported verbatim in the New York Globe, the paper of T. Thomas Fortune.

E.G. Walker was active in working for equal rights until his death. In 1886 he was elected First Vice President of the Conference of Colored Men of New England, in 1890 the President of the Colored National League, was on the executive committee of the New England section of the National Equal Rights League, and when he died he was President of the Equal Rights League in Boston.

After his mother Eliza’s death, the house on Belmont Street was inherited by Edward and his half brother Alexander (Dewson). After the removal of the family house from the site, they sold the house to Stephen Weld, which was later owned by the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Boston. Edward Walker relocated in the 1880’s to City Square in Charlestown until he moved to Beacon Hill where he died in 1901 of Pneumonia. Edward is buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in Everett Massachusetts. Mother Eliza and her second husband Alexander are buried at the Bunker Hill Burying Ground, directly behind the family house on Belmont Street.

After his death, Edward Garrison Walker was memorialized in the Colored American magazine by Pauline E. Hopkins:

“Judge Walker was an unswerving brotherly lover of his race – a love that was all-suffering, all-absorbing, all-abstaining, all-inspiring, that had vowed never to soil its hands by any compliance that would betray a brother. That was his character.”

COMMENTS

There aren't any comments yet.

Comments are closed.